The Salamander Food Web

Categories

- Accipitridae (1)

- Acrididae (1)

- Algae (2)

- Alligatoridae (1)

- Amoebidae (1)

- Amphibians (3)

- Anatidae (1)

- Anguillidae (1)

- Arachnids (2)

- Bears (2)

- Big Cats (3)

- Birds (13)

- Bovidae (5)

- Bufonidae (1)

- Camelids (1)

- Cameras (1)

- Canines (13)

- Caridea (1)

- Carnivora (10)

- Castoridae (1)

- Cats (5)

- Cebidae (1)

- Cephalopod (1)

- Cervidae (2)

- Cetacean (1)

- Chondrichthyes (1)

- Crocodilia (2)

- Crustaceans (4)

- Culicidae (1)

- Cyaneidae (1)

- Dasypodidae (1)

- Dasyurids (1)

- Deer (1)

- Delphinidae (1)

- Desktop (1)

- Didelphidae (1)

- Dinosaurs (1)

- Dogs (13)

- Dolphins (2)

- Echinoderms (1)

- Education (10)

- Elephantidae (1)

- Equine (1)

- Erethizontidae (1)

- Erinaceidae (1)

- Farming (1)

- Felidae (5)

- Fish (5)

- Food Chain (31)

- Food Web (2)

- Formicidae (1)

- Frugivore (1)

- Gaming (1)

- Gastropods (1)

- Giraffids (1)

- Great Apes (2)

- Health Conditions (3)

- Herbivore (4)

- Hi-Fi (1)

- Hippopotamidae (1)

- Hominidae (1)

- Insects (10)

- Invertebrates (2)

- Keyboards (1)

- Laptops (1)

- Leporidae (1)

- Mammals (23)

- Marsupials (4)

- Mephitidae (1)

- Microchiroptera (1)

- Mollusks (2)

- Mongoose (1)

- Muridae (1)

- Nocturnal Animals (1)

- Odobenidae (1)

- Omnivore (2)

- Phasianidae (1)

- Phocidae (1)

- Plankton (1)

- Plants (2)

- Primate (1)

- Ranidae (1)

- Reptiles (7)

- Rhinocerotidae (1)

- Rodents (5)

- Salamandridae (1)

- Scarabaeidae (1)

- Sciuridae (2)

- Sharks (1)

- Shellfish (1)

- Sound (1)

- Spheniscidae (1)

- Suidae (1)

- Superfamily Papilionoidea (1)

- Theraphosidae (1)

- What Eats (5)

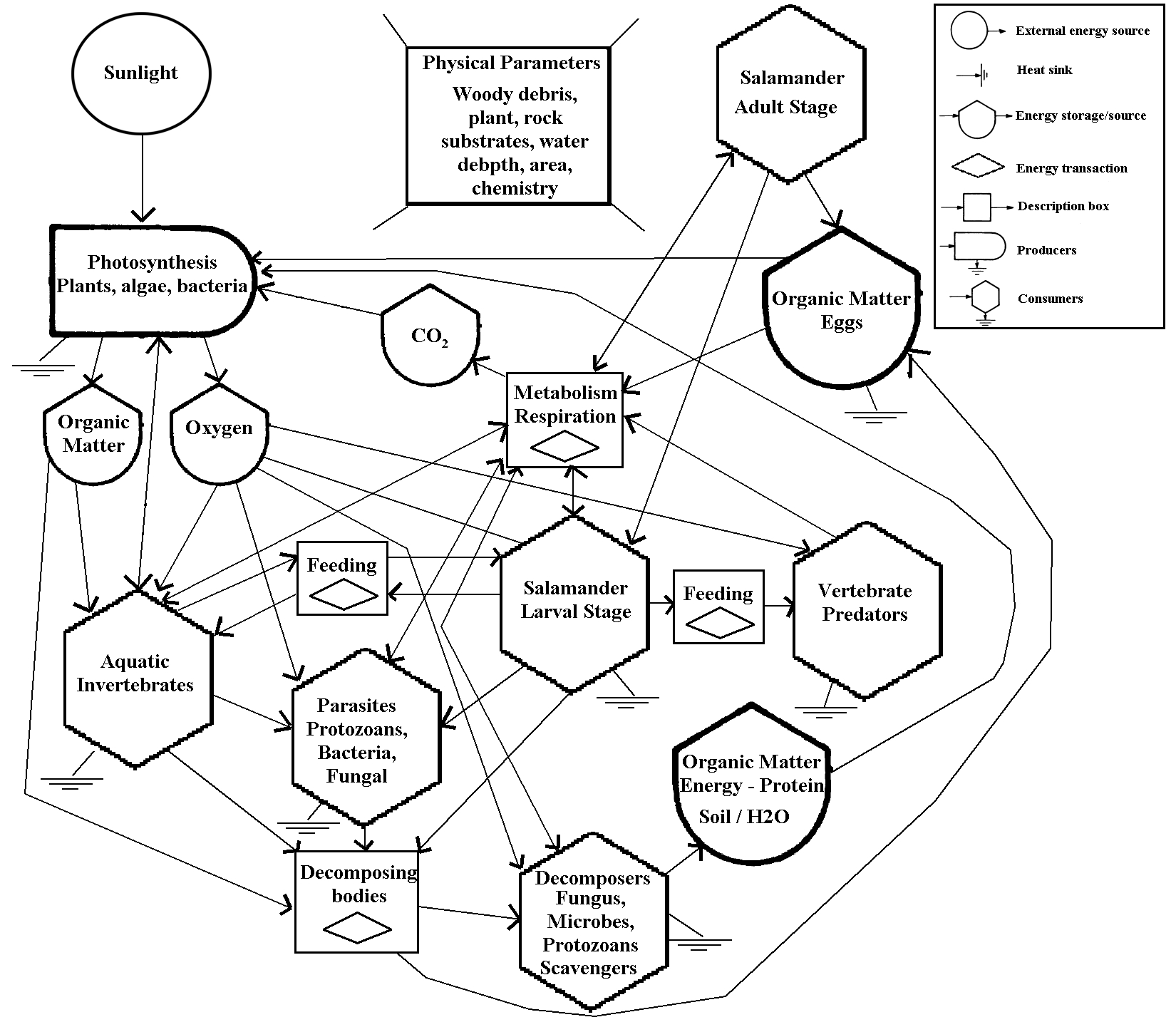

Salamanders play an integral role in forest and pond ecosystems across North America. As both predator and prey, they interact with diverse organisms spanning multiple levels of the food chain.

Understanding these intricate interrelationships provides key insights into forest ecology and guides conservation efforts for these valued amphibians.

This article explores the multifaceted food web centered around terrestrial, aquatic, and larval salamanders. We outline key prey species salamanders consume, including insects, worms, and smaller amphibians.

Larger predators, such as snakes, birds, and mammals, relying on salamanders as food sources, are also discussed. Parasites and diseases impacting salamander fitness are covered as well.

Appreciating the many connections between salamanders and other forest dwellers allows a better understanding of the ecological role of these sensitive environmental indicators.

Remember: Every Food Web Begins With Sunlight!

Table of Contents

Toggle

Salamanders as Predators

Salamanders consume a diverse array of smaller forest organisms, positioning them as important secondary consumers influencing ecosystem energy flows.

Terrestrial species hunt various insects and invertebrates under logs or leaf litter. Aquatic predators consume small fish, tadpoles, and macroinvertebrates. Larval salamander diets shift dramatically as they mature.

Larval Salamanders and Tadpoles

Larval salamanders progress through several early developmental stages, relying on different food sources. As eggs, salamanders depend on egg yolk reserves to grow over days to weeks. Recently hatched larvae subsist on even smaller organisms.

Salamander hatchings first begin feeding on microscopic life, including protists, rotifers, and small crustaceans.

Their diet diversifies by gradually incorporating larger zooplankton, including small insects, worms, newts, and salamander larvae. Larvae rays use specially adapted gills to capture drifting organisms.

As front limbs develop, larvae add actively hunted macroinvertebrate prey to their food repertoire. Clawed toes allow grasping tadpoles, snails, aquatic insect larvae or worms to move along pond bottoms or plants. Larger larvae may even consume smaller fish.

Salamander Food Web

Juvenile and Adult Salamanders

Once metamorphosing into terrestrial forms, salamanders shift from passive to active hunting by stalking insect prey on land.

Keen vision guides mature salamanders towards movement, signaling larval or adult flies, beetles, crickets, spiders, centipedes, millipedes, and other nutritious invertebrates.

Quickly extending sticky tongues allows for the capture of fast-moving land insects and smaller prey up to one-third of the salamander’s size. Small teeth or ridges help grasp and manipulate food items before swallowing them whole.

Some fully aquatic salamander species show similar predatory behaviors underwater. Fish larvae and eggs make up an important part of grown salamander diets. Large adult hellbenders opportunistically feed on crayfish, frogs, or smaller injured fish.

Ultimately, salamanders act as both predator and prey throughout their variable lifecycles. Maintaining suitable aquatic breeding and terrestrial habitat provides the foundation for their survival in balanced forest food webs.

Key Salamander Predators

Salamanders face threats from a suite of forest predators at different life stages in aquatic and land settings. Danger lurks for vulnerable eggs, larvae, and wandering adults or juveniles. Matching the diversity of salamander prey, key predators also span different animal classes.

Aquatic Predators

Salamander larvae and eggs endure heavy predation pressure from hungry fish, aquatic insects, newts, and frogs seeking soft, protein-rich food sources. Small fish like minnows readily consume delicate salamander eggs or hatchlings drifting through pond weed beds.

Various water beetles and insect larvae attack vulnerable eggs or larvae. Larger predatory diving beetles fiercely grasp passing larvae or small juveniles at pond edges.

Salamander larvae often compete directly with frog tadpoles grazing on similar tiny aquatic organisms for scarce resources. When food becomes limited, some frog tadpoles turn cannibalistic by eating the eggs and larvae of other amphibian species.

Newts also feast on aquatic salamander larvae and eggs during daily foraging activities or while migrating between breeding ponds.

Land Dwellers

On land, snakes pose the most significant predation threat to terrestrial juvenile and adult salamanders.

Garter snakes, rat snakes, ringneck snakes, and others prey regularly on amphibians. Some snakes even use pheromone-mimicking scent secretions to attract salamanders into ambush traps.

Birds leverage sharp senses of sight and hearing to snatch up ground-dwelling salamanders under shrubs or leaf litter. Thrushes, jays, crows, and flycatchers all opportunistically consume salamanders across forested habitats.

Searching mammals also grabs distracted individuals. Chipmunks, shrews, mice, foxes, and raccoons all include salamanders in their omnivorous diets.

Diseases and Parasites

In addition to visible animal predators, salamanders face less apparent threats from a range of lethal and debilitating pathogens in both aquatic and terrestrial phases. Bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic organisms have outsized influence on their host’s survival and fitness.

Chytrid Fungus Impacts

A harmful skin disease called chytridiomycosis represents a major hazard caused by chytrid fungus, impacting over 500 amphibian species globally.

Salamanders innately carry the fungus, but changing environmental factors can trigger explosive population-threatening outbreaks. Infections disrupt skin breathing and electrolyte balance, ultimately causing cardiac arrest.

Once introduced to naïve regions, chytrid outbreaks often prove catastrophic to hosts lacking natural immunity. Unfortunately, human transport of infected salamanders for the pet trade facilitates the spread of the virulent fungus between ecosystems.

Maintaining diverse microbial communities and environmental quality limits chytrid fungus effects and allows natural resistance to develop over time.

Trematode Flatworm Parasites

Aquatic salamanders commonly encounter parasitic trematode flatworms, including multiple Ribeiroia species requiring three different hosts to complete complex life cycles.

Snails serve as intermediate hosts, releasing infectious free-swimming larvae penetrating amphibian skin when contacted. Entering limb tissue, larvae form encapsulated cysts, causing missing, extra, or malformed legs to impact motility.

When consumed by waterfowl definitive hosts, adult worms reproduce, and eggs exit in feces, starting the cycle anew.

Depending on infection intensity, heavy parasite loads cause paralysis, secondary fungal or bacterial infections, or mortality at critical larval transition stages. Quickly reproducing parasite numbers when conditions align exacerbate epidemics.

External Environmental Influences

Beyond direct consumption by predators or infection by parasites, salamanders remain vulnerable to a suite of external stressors degrading freshwater and forest habitats required across their variable life histories.

Maintaining high-quality ecosystems proves essential for salamander communities to flourish.

A Cave Salamander (Eurycea lucifuga)

Aquatic Habitats

Salamanders rely on small fishless ponds and wetland pools surrounded by intact forests to breed and complete demanding larval life stages. High-quality aquatic habitats feature abundant macroinvertebrate prey supporting developing larvae and juveniles following metamorphosis.

Diverse vegetation and detritus offer refuge from predators during the day between nocturnal foraging bouts.

Environmental factors like temperature, oxygen saturation, pollutant levels, and pH strongly dictate egg, larval, and juvenile survival rates along pond margins or shallows.

Exposure to agricultural pesticides, motor oils, or road salts quickly damages fragile gilled larvae. Acidification or drying from climate change threatens small wetland habitats and the uniquely adapted species relying upon them across seasons.

Woodlands and Forests

Mature forests with deep leaf litter layers, woody debris, lush understory vegetation, and rocky hiding places support thriving terrestrial salamander abundance and diversity.

By consuming insects, worms, snails, and vegetation, forest salamanders influence soil nutrient profiles and ecosystem services through waste deposition. In turn, mycorrhizal fungi and microbes recycle salamander-derived nutrients to promote forest plant growth.

Leaf litter moisture content largely determines favorable salamander foraging and migratory conditions on land. Damp organic soils host far richer terrestrial invertebrate prey options compared to dry habitats.

Light snow cover helps conserve soil moisture while blocking deep frost penetration, threatening hibernating salamanders overwintering belowground in burrows or natural crevices.

Conclusion

Salamanders occupy a central role in forest and freshwater food webs as both predator and prey. Their multifaceted lifecycles tie in with diverse organisms, from microscopic parasites to large mammals across ecosystems.

Maintaining high-quality breeding wetlands and connected woodlands proves essential for supporting resilient salamander communities.

As secondary consumers, salamanders influence insect and invertebrate populations which shape plant growth. As prey for snakes, birds, and mammals, salamanders directly and indirectly impact numerous species relying on forests for survival.