What Eats A Salamander?

Categories

- Accipitridae (1)

- Acrididae (1)

- Algae (2)

- Alligatoridae (1)

- Amoebidae (1)

- Amphibians (3)

- Anatidae (1)

- Anguillidae (1)

- Arachnids (2)

- Bears (2)

- Big Cats (3)

- Birds (13)

- Bovidae (5)

- Bufonidae (1)

- Camelids (1)

- Cameras (1)

- Canines (13)

- Caridea (1)

- Carnivora (10)

- Castoridae (1)

- Cats (5)

- Cebidae (1)

- Cephalopod (1)

- Cervidae (2)

- Cetacean (1)

- Chondrichthyes (1)

- Crocodilia (2)

- Crustaceans (4)

- Culicidae (1)

- Cyaneidae (1)

- Dasypodidae (1)

- Dasyurids (1)

- Deer (1)

- Delphinidae (1)

- Desktop (1)

- Didelphidae (1)

- Dinosaurs (1)

- Dogs (13)

- Dolphins (2)

- Echinoderms (1)

- Education (10)

- Elephantidae (1)

- Equine (1)

- Erethizontidae (1)

- Erinaceidae (1)

- Farming (1)

- Felidae (5)

- Fish (5)

- Food Chain (31)

- Food Web (2)

- Formicidae (1)

- Frugivore (1)

- Gaming (1)

- Gastropods (1)

- Giraffids (1)

- Great Apes (2)

- Health Conditions (3)

- Herbivore (4)

- Hi-Fi (1)

- Hippopotamidae (1)

- Hominidae (1)

- Insects (10)

- Invertebrates (2)

- Keyboards (1)

- Laptops (1)

- Leporidae (1)

- Mammals (23)

- Marsupials (4)

- Mephitidae (1)

- Microchiroptera (1)

- Mollusks (2)

- Mongoose (1)

- Muridae (1)

- Nocturnal Animals (1)

- Odobenidae (1)

- Omnivore (2)

- Phasianidae (1)

- Phocidae (1)

- Plankton (1)

- Plants (2)

- Primate (1)

- Ranidae (1)

- Reptiles (7)

- Rhinocerotidae (1)

- Rodents (5)

- Salamandridae (1)

- Scarabaeidae (1)

- Sciuridae (2)

- Sharks (1)

- Shellfish (1)

- Sound (1)

- Spheniscidae (1)

- Suidae (1)

- Superfamily Papilionoidea (1)

- Theraphosidae (1)

- What Eats (5)

Salamanders are small amphibians that have adapted to live both on land and in the water. Their moist, permeable skin makes them vulnerable to desiccation, so they are most active in damp environments like forests, swamps, and near streams and ponds.

Salamanders play an important role as both predator and prey in these ecosystems. But as prey, salamanders have many different animals that like to eat them.

Birds Hunt Salamanders in Forest and Wetland Habitats

With a diverse array of birds inhabiting salamander ecosystems, these amphibians are constantly threatened by the skies. Birds that prey on salamanders include herons, bitterns, crows, jays, magpies, grouse, turkeys, hawks, and owls.

Table of Contents

ToggleWading birds like herons and bitterns stalk salamanders camouflaged among vegetation near water. The bitterns’ lightning strike with their spear-like bill makes them effective hunters.

Crows, jays, magpies, grouse, and turkeys snatch up any salamanders they come across while foraging on the forest floor.

The most dangerous aerial predators for salamanders are birds of prey. Hawks scan from high perches, watching for movement below before swooping in for the kill. Powerful talons provide hawks the ability to snatch up and carry adult salamanders with ease.

Stealthy owls employ a similar strategy, using their specialized feathers to fly silently as they hunt at night when many salamanders are most active.

While adult salamanders may prove difficult for some bird species to handle, eggs and larvae make easy pickings. All sizes of birds consume these vulnerable young, often in large quantities at breeding sites.

This predation shapes salamander behavior, driving them to hide eggs or provide parental care until larvae grow large enough to evade the threat from birds.

Snakes Track Salamanders on Land and in Water

Like winged predators, snakes employ diverse hunting strategies to consume salamanders in many habitats. Garter snakes, water snakes, rat snakes, king snakes, and others all prey on various salamander species.

Generalist snakes, like the common garter, feast on whatever small animals they come across, including young salamanders. Specialists like the red salamander hunter focus specifically on salamander prey.

Species that frequent aquatic areas pose the greatest overall threat to salamander populations. Snakes such as northern water snakes and common watersnakes locate salamanders in forest pools, along stream banks, and beneath logs or rocks across wetlands and riparian zones.

Here, they ambush both larvae and adults. Some snakes even target salamander egg masses, providing an abundant source of food.

With a highly developed sense of smell, snakes easily follow salamander scent trails. Forked tongues gather chemical particles from the air or ground to lead snakes to their quarry.

Powerful jaws allow snakes to swallow salamanders whole, aided by the flexibility of their lower jaws, skin, throat, and body muscles. These adaptations make snakes efficient and effective predators in all life stages of salamanders across their habitats.

Hungry Fish Lurk Below in Salamander Aquatic Habitats

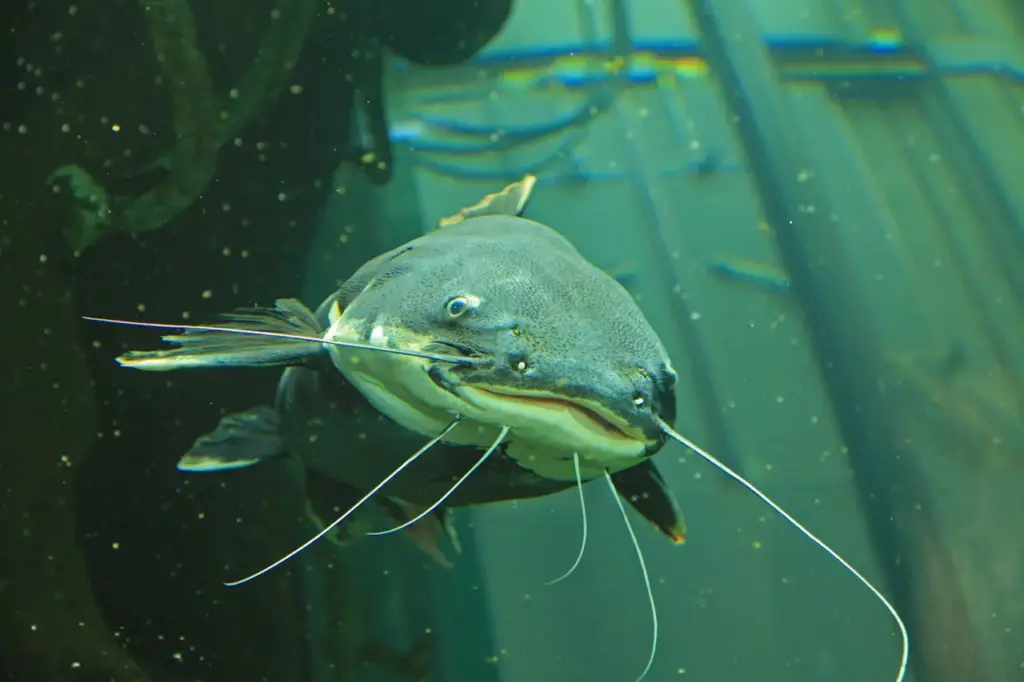

Constantly contending with aerial and terrestrial dangers, salamanders also face predatory fish while inhabiting ponds, streams, and wetlands. Species known to prey on salamanders include largemouth bass, perch, trout, catfish, sunfish, and others.

These fish ambush aquatic salamanders as they swim to the surface to breathe or stay buoyed. Salamander larvae lack strong swimming skills early on, making them easy prey for quick, aggressive fish.

Feeding catfish use external taste receptors lining their jaws to sniff out hidden salamanders buried in muddy substrates. Crafty trout corral salamander larvae are pushed into tight bait balls to gorge more effectively.

Sunfish and perch patrol drop-offs or dense submerged vegetation, waiting to attack salamanders as they pass by. Armored with sharp teeth and powerful jaws, predatory fish easily puncture soft salamander flesh and tear them apart.

For some fish, eggs provide their main salamander food source. Largemouth bass, in particular, key in on eggs, tracking down each precious ball the female lays across a breeding site.

Schools of smaller fish also contribute to consuming huge numbers of vulnerable eggs and newly hatched larvae.

Managing to survive fish predation long enough to reach adult size provides salamanders a better, but not guaranteed, chance of evading their predators from below.

Amphibians and Reptiles Threaten Salamanders on Land and Water

Interestingly, some of the biggest predators of salamanders come from their branch of the vertebrate family tree. Frogs, toads, and other salamanders all view various species as food options when opportunities present themselves.

Young frogs and developing larvae provide the most common source of amphibian prey. Aquatic giants like bullfrogs and mudpuppies eat mostly eggs and larvae but also threaten the terrestrial stages of small species.

Hiding on stream bottoms, the gargantuan hellbender salamander ambushes younger, more vulnerable species that share rocky aquatic habitats. Ensnared between their powerful jaws, few creatures escape hellbenders’ vice-like grip.

Equally dangerous, giant tiger salamanders occupy temporary wetlands, consuming hundreds of eggs and larvae of other breeding amphibians. Their huge gaps allow them to swallow multiple bullfrog tadpoles at once!

Outside of amphibian dangers, reptiles also take their share of the salamander buffet. Aquatic turtles snap up larvae and adults while powerful jaws and sharp beaks make quick work of their slimy skin and bones.

No environment provides complete protection as land-dwelling lizards like skinks raid salamander nest sites. Their preference for eggs makes breeding attempts a risky endeavor.

Mammals Fill a Diversity of Roles Among Salamander Predators

All sizes of mammals, from tiny shrews to massive bears, find salamanders a tasty supplement to their diet across a variety of habitats. As generalized insectivores, shrews eat any small invertebrates or vertebrates in their path, including juvenile salamanders.

Their fast metabolism demands excessive food consumption, driving shrews to consume over double their body weight daily.

At home on land or in water, elongate weasel relatives like mink, marten, otter, and wolverines all threaten salamanders during their hunting forays.

Keen senses easily detect these reclusive amphibians no matter how well-hidden they may be under rocks or logs. Dextrous claws make pulling salamanders from crevices no match against these determined predators.

Reaching larger sizes, mammalian omnivores present even greater danger with their intelligence and versatility. Clever raccoons, skunks, and opossums all know how to locate salamander buffets.

Following vocalizations of amorous males leads them to vernal pools during peak breeding. Here, eggs are available by the hundreds as they greedily move from clutch to clutch. Even the mighty black bear lumbers over to partake in this ephemeral delicacy when discovered.

Despite the diversity of skilled hunters, salamanders somehow continue surviving thanks to key adaptations that offer some defense against predation.

Their cryptic coloration, ability to detach tails, noxious skin secretions, and tremendous regenerative capacity enable ongoing endurance of consistent threats. But the odds seem continually stacked against their long-term persistence.

Conclusion

Salamanders occupy an unenviable position in nature – too slow to flee from trouble and having to navigate between worlds to complete their complex life cycles.

Myriad specialists and opportunistic predators from birds, snakes, fish, amphibians, and mammals take advantage of every chance to consume these delicate creatures.

Only by breeding prolifically and relying on defensive adaptions can salamanders hope to run this predatory gauntlet generation after generation. Though with many amphibian species declining, even organisms so well-adapted to threats face uncertainty in a changing world.