What Eats An Amoeba?

Categories

- Accipitridae (1)

- Acrididae (1)

- Algae (2)

- Alligatoridae (1)

- Amoebidae (1)

- Amphibians (3)

- Anatidae (1)

- Anguillidae (1)

- Arachnids (2)

- Bears (2)

- Big Cats (3)

- Birds (13)

- Bovidae (5)

- Bufonidae (1)

- Camelids (1)

- Cameras (1)

- Canines (13)

- Caridea (1)

- Carnivora (10)

- Castoridae (1)

- Cats (5)

- Cebidae (1)

- Cephalopod (1)

- Cervidae (2)

- Cetacean (1)

- Chondrichthyes (1)

- Crocodilia (2)

- Crustaceans (4)

- Culicidae (1)

- Cyaneidae (1)

- Dasypodidae (1)

- Dasyurids (1)

- Deer (1)

- Delphinidae (1)

- Desktop (1)

- Didelphidae (1)

- Dinosaurs (1)

- Dogs (13)

- Dolphins (2)

- Echinoderms (1)

- Education (10)

- Elephantidae (1)

- Equine (1)

- Erethizontidae (1)

- Erinaceidae (1)

- Farming (1)

- Felidae (5)

- Fish (5)

- Food Chain (31)

- Food Web (2)

- Formicidae (1)

- Frugivore (1)

- Gaming (1)

- Gastropods (1)

- Giraffids (1)

- Great Apes (2)

- Health Conditions (3)

- Herbivore (4)

- Hi-Fi (1)

- Hippopotamidae (1)

- Hominidae (1)

- Insects (10)

- Invertebrates (2)

- Keyboards (1)

- Laptops (1)

- Leporidae (1)

- Mammals (23)

- Marsupials (4)

- Mephitidae (1)

- Microchiroptera (1)

- Mollusks (2)

- Mongoose (1)

- Muridae (1)

- Nocturnal Animals (1)

- Odobenidae (1)

- Omnivore (2)

- Phasianidae (1)

- Phocidae (1)

- Plankton (1)

- Plants (2)

- Primate (1)

- Ranidae (1)

- Reptiles (7)

- Rhinocerotidae (1)

- Rodents (5)

- Salamandridae (1)

- Scarabaeidae (1)

- Sciuridae (2)

- Sharks (1)

- Shellfish (1)

- Sound (1)

- Spheniscidae (1)

- Suidae (1)

- Superfamily Papilionoidea (1)

- Theraphosidae (1)

- What Eats (5)

Amoebas are unicellular protists that morph into a variety of shapes by extending and retracting pseudopod limbs from their plasma membranes. Ranging in length from 0.1mm to 0.5mm, these master adaptors inhabit aqueous environments and moist soils across the planet.

As omnipresent microbes, amoebas play a fundamental role in ecological food chains. They graze primarily on bacteria, algae, plant cells, and other protists. But they also fall prey themselves to an array of predators.

Examining what eats microscopic amoebas provides insight into the complexities of largely invisible microbial ecosystems operating across scales.

Table of Contents

Toggle

Predatory Protists

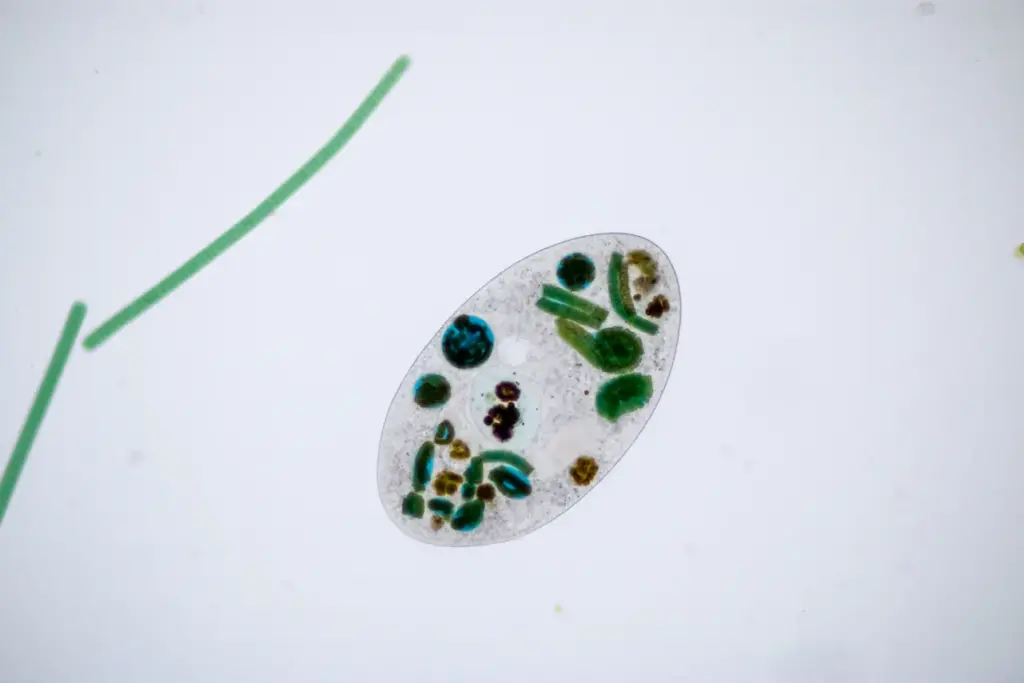

The most common predators of amoebas are other hungry protists. These single-celled eukaryotes consume bacteria, algae, and other protists like amoebas. Examples include flagellates and ciliates like paramecia, stentors, and vorticella.

Slightly more complex than standard amoebas, these predators detect chemical cues released from amoebas and other protist prey. Equipped with specialized structures, they mobilize to intercept and then capture target microbes.

Paramecia and other ciliates utilize hair-like organelles called cilia to cover their outer membrane and generate a vortex pulling in particles.

This current sweeps amoebas and other nutritious prey into the Gullet, where it becomes encapsulated into a food vacuole internally. Powerful enzymes break down the engulfed organisms to extract energy and nutrients for absorption.

Stentors and vorticella employ similar tactics but rely on tentacle-like cilia clustered around an adhesive disk to catch free-floating microbes by adhesion or direct conveying to an ingestion opening.

Grappling hooks extend out when these sessile hunters sense a potential meal within range. The waving cilia allow stunning and retrieval of unsuspecting amoebas and other prey wandering past.

For giant amoebas like Chaos carolinense spanning lengths over 5mm, a group of predatory testate amoebas called Difflugiids collaborate to attack and dismantle massive cells through repeated cycles of partially ingesting segments.

These chunking efforts combine to gradually reduce the jumbo amoebas down to a size digestible for individual protist consumption.

As competitors and opportunistic consumers, predatory protists keep watch for neighboring amoebas to make meals of. They regulate populations and account for a significant proportion of overall amoeba mortality within occupied ecosystems through direct predation.

Microscopic Animals

Beyond unicellular grazers, various micro-animals also feed on amoebas as prey. Nematodes and tardigrades both utilize stylet mouthparts to spear and then extract nutrients from amoebas abundant in shared habitats.

Aquatic relatives like rotifers and gastrotrichs indulge more passively through filtering intake currents that capture small protists, including amoebas.

Nematodes thrive ubiquitously from deep-sea sediments to moist soils, where they consume bacteria, algae, fungi, ciliates, other nematodes, and available protists.

Equipped with a hollow tooth-like device called a stylet, bacteria-eating species puncture amoeba cell walls and then siphon out cytoplasm and organelles as sustenance. Regulating factors within their digestive tracts prevent overconsumption of fluids during harvest.

Microscopic tardigrades prove even more voracious. Possessing a disproportionately expandable pharynx lined with dagger-like stylets, “water bears” feed by puncturing captured prey before sucking out juices like a Slurpee.

Amoebas wander into range only to be grasped and then tapped into vehicles of consumption. Luckily for amoebas, tardigrades focus mainly on meatier animal prey when available rather than plant material.

Active suspension feeders also take their cut of passing amoebas floating through aquatic systems. Rotifers utilize cilia-covered crowns to generate vortex currents that steer microbes into their gaping mouths.

Gastrotrichs rely on adhesive tubes coating much of their bodies to ensnare prey. Both feature contractile pharynxes facilitating nutritious amoeba consumption.

Fungi

Fungi comprise another threat, preying on amoebas patrolling shared habitats. Yeasts like Candida albicans that frequently inhabit animal guts opportunistically exploit amoebas and bacteria encountered while thriving on mucosal surfaces.

Filamentous fungi and zoosporic fungi employ more intricate adaptations tailored for trapping microbial meals.

Within fungal phyla, Zygomycota and Chytridiomycota exist orders featuring species that capture prey on microscopic organisms. Zoopagales fungi produce self-assembling collars that tighten around target cells attempting to swim through.

Holdfast hyphae employ similar noose-like snares that latch onto protists, including amoebas, contacting trailing filaments. Once captured, penetrating hyphae breach cell walls to access nutritious interiors.

Aquatic fungi utilize extrusive organelles termed rhizoids for adhering to actively swimming passersby. Once amoebas or other protists contact sticky filaments, the fungus reels them in using contractile elements within the holdfast base.

This seals fate through forced surface attachment, and eventually, weakened cells lead to complete parasitism. For fungi paired in symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic algae or cyanobacteria, ensnaring surplus protists provide supplementary nutrients when light levels drop and food production declines.

Fungi transit from benign habitat occupants to active consumers based on the availability of vulnerable drifting amoebas within a detection radius.

Bacteria

Bacteria considered predators of amoebas employ clever mechanisms, turning defenses into digestible offenses. Myxobacteria notorious for secreting antimicrobial compounds also unleash lethal chemicals, triggering suicide in target cells.

Exposure causes amoeba membranes to disintegrate during compromised stress reactions. Lysed cell contents then get soaked up as rich bacterial food sources.

But the most savage bacterial predator of amoebas deploys an internal assault strategy. Bdellovibrio and like organisms (BALOs) infiltrate and then hollow out host cells through replicated digestion.

Equipped with enzymes to degrade cell walls, BALOs bore into detected amoebas and other Gram-negative bacteria. Waves of clones unleash internally until resources expire in the collapsing cell.

This releases BALOs to find new targets by sensing chemotaxis signals of potential prey. In the process amoebas and many other microbes fall victim to bacterial predators infinitely smaller yet equally ruthless.

What BALOs lack in size compared to amoebas, they compensate through proficient localization and identification of vulnerable organisms.

Humans

While not directly preying on amoebas themselves, human activities profoundly shape the fate of protist populations. Anthropogenic organ pollutants like pharmaceuticals, hygiene chemicals, pesticides, and hydrocarbons enter natural ecosystems with increasing regularity.

Many factors toxic to animals and plants in higher concentrations also detrimentally impact amoebas and cellular processes. Low levels of triclosan found in medical sanitizers and household cleaners prove tolerable to animals but impede amoeba feeding over time.

Chlorpyrifos pesticide runoff from lawns disrupts cytoskeletal structure. Modeling on glyphosate herbicides reveals inhibition of phagocytosis and depressed reproductive activity in tested amoeba cultures.

And interaction rates with true predators rise in correlation with human disturbance regimes. Higher temperature, nutrient spikes, and humidity changes all enable elevated microbial metabolism, benefiting predatory protists, fungi, and bacteria.

Behaviors like enhanced hunting, capture, and replication increase under these conditions. The collective influence drastically alters natural checks and balances between predators and prey.

While nearly invisible to the human eye, microbial food webs determine higher-level ecosystem function and services. Disrupting microscopic interactions manifests in eventually weakened environmental resilience across scales.

But understanding connections helps foster responsible actions supporting our interconnected world even down to the tiniest levels.

Conclusion

Amoebas perform an essential service within ecological systems as nutrient recyclers and food web foundations. Yet despite lacking complexity in cellular structure, diverse organisms exploit their role as prey.

Competition and predation keep ambling amoeba travelers in check as opportunistic protists stalk them through shared terrain.

Microscopic worms, bears, flies, and spiders view amoebas as just another meal attacking without hesitation. Fungal snares lie hidden, awaiting errant contact by nutrient-packed protists wandering past their sticky traplines.

Predatory bacteria scheme the ultimate betrayal, volunteering genocide to competing clones by hijacking replicative advantage against victims from within.